Along the "Old Line" of the L&N, north of Birmingham

Bar-B-Que and the Warrior

Mineral RR

I

moved to Birmingham in 1992 from

Nashville and was immediately struck by

the clear historical presence of so many

railroads.

Being from Nashville, I was sort

of an L&N fan, but Nashville was

sort of a “one railroad town”.

I

learned that Bar-B-Que plays an

important role in the day to day life of

folks in Alabama, along with church and

uh, football.

I did a lot of work in my career

for the Highway Department and soon

heard about the Top Hat Bar-B-Que in the

south end of Blount County.

So, not long after I moved I had

a chance to be in that area and stopped

in for a late lunch.

The

Top Hat wasn’t busy that day, and I

got to talking to the “pit man”.

You know that you have to get up

pretty early to start a day’s run of

butts and shoulders.

Some mornings he told me, he

would be working alone, very early.

“It’s the strangest thing”,

he said, “but some mornings, real

early, I’d swear that I hear an old

time steam engine goin’ by – right

by, close – you know?

And I hear that old steam whistle

just talking…”

He finished up with “I just

hears it sometimes, not all times –

sure do sound lonesome…”

Sometimes where I live, I can hear the CSX trains on the mainline not so far from my house and I would swear that the diesel horn was a steam whistle… I understand the Pit Man’s story.

|

|

1889 USGS map from USGS Topo View website. |

A

while back, Marv Clemons, James Lowery

and the author took a field trip to the

Helena Museum to talk with Ken Penhale

about railroad history in the area.

Ken’s people came from the

mines in Cornwall to the mines in Helena

in the 1870’s.

That goes back to the roots of

Birmingham’s industrial and railroad

history.

Helena was near the end of track

through the end of the Civil War.

Coal mined near Helena, was

brought on a spur to the interim

mainline of what became the South and

North Alabama’s mainline to Birmingham

– after the War.

From

Helena, the coal was taken south to the

Alabama and Tennessee River Railroad,

later the Selma, Rome and Dalton, and

shipped to Selma for use in the

foundries there.

When the Eureka Company was

formed (at Oxmoor furnace) to experiment

with making iron using coke instead of

charcoal, the coal came from Helena

mines.

Upon the success of the

experiment in 1876, a hundred coke ovens

were built at Helena – the ruins are

still there, adjacent to the

Hillsborough Subdivision.

And there are other old ovens

nearby on Buck Creek – Ken Penhale

knows all about the area.

Go visit the museum at Helena!

At

the time of the Eureka experiment,

carried out at Oxmoor Furnace,

Birmingham was hardly even born.

There had been a financial “panic”

in 1873, and the newly built railroad

struggled for lack of freight much less

passengers.

As Ethel Armes says in her

landmark history “The Story of Coal

and Iron in Alabama”, no one traveled

much in Alabama in those days.

And there was little capital for

mines.

She

also tells us that at this time, there

were only a few coal mines opened in the

area that became the Birmingham

District.

The mines at Helena, some of

which dated before the War, were located

in the Cahaba Coal Field.

The other mines, brand new at the

time, were also tried for coking coal.

But these mines were far to the

north around the Jefferson and Blount

County line.

That was called the Browne coal

seam of the Warrior Basin, later changed

to the Pratt Seam.

When

the South & North Alabama Railroad

was completed north of what was to be

Birmingham, toward Decatur, the railroad

was in dire financial shape.

In fact the founding of

Birmingham hung in the balance in 1871

because the new company couldn’t raise

the money to pay interest on the State

backed bonds.

A competing railroad, the

Southwest and Northeast, wanted to ship

the area’s mineral wealth to

Chattanooga.

Just in the nick of time, a man

named James Sloss stepped in and offered

a deal to the L&N Railroad which had

been extended south to Nashville.

Sloss offered his Nashville &

Decatur line, and urged the S&NA

backers to offer their line, still

incomplete, to the L&N as a “lease

and build” deal.

The

short version of this story is that the

deal was worked out in Louisville,

finally, and the L&N stepped in to

provide capital to pay the interest on

the bonds, and o provide for the

completion of the line from Elyton,

Birmingham’s predecessor to Decatur.

This was a win-win-win for all

involved as it provided a logical

extension of the L&N toward the

Gulf, saved the S&NA and allowed

James Sloss to move toward a Birmingham

where he entered the iron business.

That is another story.

But,

since the finances were so constrained,

the S&NA’s Chief Engineer, John

Milner, who knew better, had no choice

but to direct the contractor “more

curves, more curves, more stiff grade”

as the line was built north in the hills

and valley of Jefferson and Blount

County toward Decatur.

So, every effort was made to

avoid cuts and fills, to avoid tunnels

and to minimize bridges.

But the line was completed in

1872 and traffic, as little as there

was, could move from Montgomery to

Nashville with the L&N as lease

holder of what was called the S&NA

Division for many years.

But the line and grade were

rough!

So,

in the latter years of the 19th

Century Birmingham slowly started to

become the workshop town envisioned by

its founders who were also the leaders

of the S&NA.

The S&NA’s mainline soon

had new spurs being extended to serve

mining efforts of the pioneer coal

entrepreneurs.

This included mines in the area

whose towns became Warrior, Kimberly and

Morris as well as colorful names like

Majestic and New Castle to name a few.

One of the things that the L&N did showed wise business acumen by its leader, Milton Smith. Smith was willing to support the extension of lines to mining areas. Different arrangements could be worked out, but a typical approach was for the L&N to “lend” the hardware to build the rail spur, as well as capital to pay for grading and draining the new line. At the time, the 1890’s and early 1900’s terms might be 6-7% interest for the mining company and the interim use of adequate hardware from the railroad.

It is noted that subsequently, and about the time period of the story below (c. 1911-1915), the L&N determined the need to "fix" problems with alignment and grade around Birmingham and all the way to Nashville, as well as double tracking this line, due to the heavy traffic that had developed due to Birmingham's significant growth. That work is a story in itself.

Herein

lies the real subject of this story –

an example of one such effort by a

railroad that the author had not heard

of until recently – The Warrior

Mineral RR.

I had certainly heard of the

Birmingham Mineral, and that was our

reason to visit Ken Penhale, but I had

never heard of the Warrior Mineral.

You’ve heard that a picture is worth a thousand words. This story involves three pictures, provided to Marv Clemons by one of the R&LHS Mid South Chapter members, [the late] Larry Kelpke. Three pictures and three captions on the back were all that there was to start solving a puzzle about coal mining and railroad history – an example like so many.

We pretty well knew where Warrior was, on the “old” S&NA mainline. The author had heard of Nyota, and a search revealed it to be on the “new” mainline (c. 1915) of the L&N, somewhat to the east. The image shows that “Louise” bears the name “Warrior Black Creek Coal Co" (WBCCC). Research indicated that the WBCCC was active in the era of WWI and included members of the Moss family – quite a few of them in fact. There were three mines opened by the company, Liberty, No. 2 and Carbon. This was found in the Coal Directory of 1920, although the directory didn’t say a word about Louise, only referring to mule and rope haulage. These directories typically did say if the company owned any locomotives, but for reasons we don’t know, Louise didn’t make the directory. But we know she was there, cause we have pictures.

Now the story expands a little bit.

We have mention of the L&N

Railroad, the Moss-McCormack Coal

Company, and the Sibleyville Brick

Company. Both images give us a time frame

of 1915.

Research yielded the

Moss-McCormack Coal Company (MMCC) as a

successor to the WBCCC between 1920 and

1921 editions of the Coal Directory.

This series of Directories

covered the entire United States, and

was published by the Keystone Publishing

Co of Pittsburgh, and was found through

Google Books.

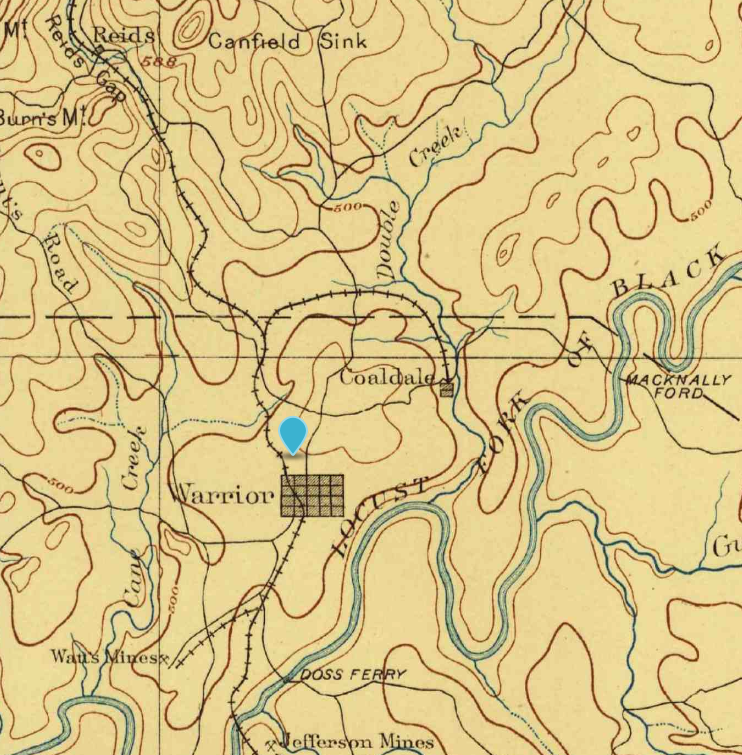

When

faced with research of this type, maps

are a key tool in the effort.

One source is the United States

Geological Survey, USGS, and these maps

are available free on line at the

“USGS Map Store” website.

For the Birmingham area, the

author knew that maps might be found in

three time frames, c. 1890, c. 1907 and

after that, sometimes the 1930’s and

sometimes the 1950’s and newer.

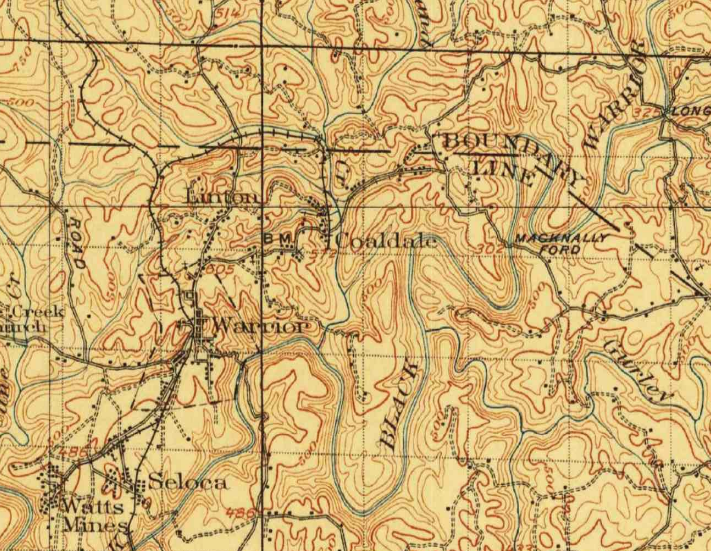

A wonderful map was found of the

area around Warrior, dated 1907.

This map image shows the

“old” S&NA/L&N mainline

through Warrior and shows two obvious

spurs to Watts Mines and to Coaldale.

The place name “Nyota” is not

shown on this map which indicates that

it was obscure or that it “hadn’t

happened yet” – one doesn’t always

know which.

But Nyota does show on the newer

USGS maps “sitting straddle” on the

“new” L&N mainline.

Nyota would be in toward the

upper right hand corner, toward the

“WA” in Warrior, above the “Y”

in Boundary (in the 1907 map below).

|

|

| US Geological Survey (USGS) map dated 1907. Found on USGS web site via Topo View. |

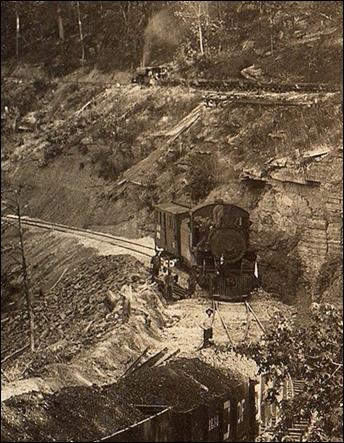

The caption reads, “Coal train of Moss-McCormack at Nyota, AL about 1914. Loco in background with a box car indicates some general merchandise hauling. Warrior River to left.” [Closer review makes this “boxcar” out to be a work car or a homemade caboose. |

“When in doubt, ask Google”, is another tool of the intrepid rail history “researcher” (nut). So, Google was asked about the “Warrior and Nyota” as well as the “Warrior Black Creek” coal company. The company name search results included a reference to the company incorporation charter, which in turn led to the Secretary of State’s online business records archive. Oh my, this website is a treasure trove of arcane data. For a $20 bill (credit card) the researcher downloaded documents from 1911 and 1912 about WBCCC which add much to our puzzle and the story behind it.

Milton Smith would have been proud! In fact he might have approved this business deal. The documents indicate that the WBCCC had a railroad called the Warrior Mineral RR. The Warrior Mineral desired to extend a spur to its parent’s new mine, but lacked the resources. The parent also lacked the resources, and so turned to the S&NA RR (Division of the L&N) for “aid”. Aid was forthcoming in the amount of $40,000 as well as “lend”-ing the railroad all the necessary hardware to build the line.

Of

more help was a solid location on this

venture.

First, contract document states

that track will be extended from the

Hogeland Br of the Linton Br of the

S&NA R.

From our 1907 map we can see

Hogeland Creek and we can see Linton, so

the names of the spurs make sense.

And the other location is “hard

stuff” – the “NW Qtr. of the NW

Qtr. of Section 8, Township 14S, Range 2

West”.

Without going into all the

details, this narrows the site down to

40 acres on the USGS map of 1907.

You just have to know how to read

the map.

And 40 acres is a pretty specific

area on a map of this scale.

This form of land reference is

called Range and Township and is used

throughout Alabama, which is a very good

thing for this type research.

The plot certainly began to thicken at this point. In looking at our 1907 map and the range & township location, this was nowhere near the Warrior River. Granted, it’s in the neighborhood, but we see no track alongside the Warrior River. What other maps might show this information?

|

|

|

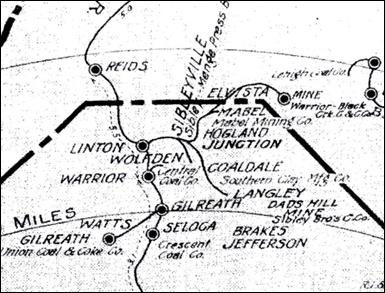

Segment from Kelly's 1905 "Mines, Railroads and Industries" map. |

The

Mid-South Chapter of the R&LHS sells

maps to its members as well as the

general public.

One of these is Kelly’s 1905

Mine, Railroad and Industrial Map.

It is a wonderful resource and

proved helpful in this puzzle.

This map doesn’t show “Nyota”

but it does show “Sibleyville” and

the brick company from caption two.

It shows Coaldale, and Hog[e]land

Junction, referred to in the railroad

loan contract and it shows a mine far

off to the right, labeled Warrior-Black

Creek Coal Company.

But is doesn’t show the river

– that is, this map doesn’t show any

rivers, so it is of no help there.

More

research was in order.

The author dug deep and realized

he had a mine directory downloaded

several years ago, dated 1986, that

ostensibly documents “every” coal

mine in Alabama with data on location,

ownership and mine name.

Skipping some details, this led

to a search of Blount County properties

of the Moss-McCormack Coal Company,

labeled “Upper Creek” with range

& township locations.

When these were plotted, low and

behold, they were close to the Warrior

River!

They were also close to the “mine”

shown on Kelly’s map labeled for the

WBCCC.

Another

resource collected by the author are a

series of aerial photos taken in 1940-41

by the Soil Conservation Service (SCS),

now a component of the Natural Resources

Conservation Service (NCRS).

But the collection only covers

Jefferson County, and a little bit over

the line.

Would there be any coverage?

Fortunately, the answer was “yes”

and it was exactly the coverage needed.

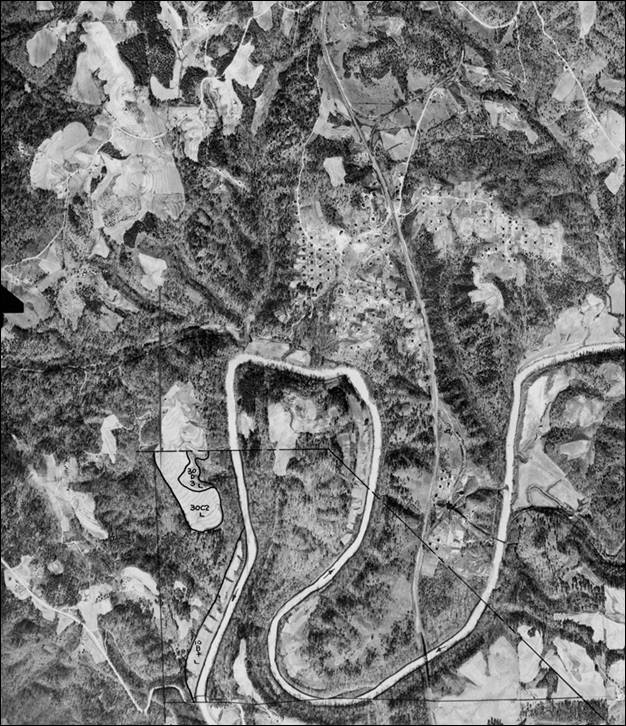

This

image is dated 2/17/1941 and shows a

large coal mining property, as indicated

by the many workers houses and telltale

shape of spoils piles.

The line running up and down the

picture (north-south) is the “new”

L&N mainline.

If you look closely you may be

able to see a “wye” track near the

top to the right of the mainline.

That is the location designated

“Nyota” on modern USGS maps.

What

is more important is the line in the

trees coming in from the left, and going

just above the bend in the river, in the

middle of the picture.

This line is a rail spur, and it

is “next to the Warrior River” just

as shown in picture number 3!

A

detail from image three shows the

“Louise” in the background on a

tramway on the bluff. There seems to be

a semblance of a coal dump (slide) to

enable the tramcars to dump from the

bluff to the hoppers or gondolas below

on the spur.

Putting

all the pieces of the puzzle together,

confirms that the rail spur for which

the company borrowed $40,000 from the

S&NA/L&N extended from the

Linton Spur to Nyota and it does end up

next to the river as shown in the image.

By the time of the 1941 aerial it

is pretty clear that the rail spur was

likely abandoned.

And why not – the main line of

the Old Reliable ran right through the

middle of the mines at Nyota!

So,

what became of the spur when the

mainline was relocated?

Kincaid Herr, in his landmark

L&N History tells us that this work

was done around Birmingham between

1911

and 1914.

And the line from New Castle to

Bangor, which required the 2,200 foot

Hayden Tunnel, was “completed by

November 15, 1914.”

It certainly appears that image

three, dated 1914 is a brand new line,

freshly graded and ballasted, recently

cut trees and blasted rock in evidence.

So, did the coal company borrow

$40,000 only to complete the line in

time for the L&N to relocate the

mainline right through the area served

by the mortgaged spur track?

Did the L&N do the mine

company dirty?

Did the spur get some use to

amortize it before being abandoned?

1911

and 1914.

And the line from New Castle to

Bangor, which required the 2,200 foot

Hayden Tunnel, was “completed by

November 15, 1914.”

It certainly appears that image

three, dated 1914 is a brand new line,

freshly graded and ballasted, recently

cut trees and blasted rock in evidence.

So, did the coal company borrow

$40,000 only to complete the line in

time for the L&N to relocate the

mainline right through the area served

by the mortgaged spur track?

Did the L&N do the mine

company dirty?

Did the spur get some use to

amortize it before being abandoned?

We

don’t know at this point in our puzzle

solving.

Staring at the 1941 (right) aerial there

appears to be a mine tipple served by

the tramway “Louise” that would not

have been readily accessible to the

L&N mainline.

And there appears to be a formal

tipple from the tramway to the spur

track – maybe!

A field trip to the woods might

help tell the tale.

More research may help explain

the timing of improvements at Nyota.

But

the L&N did relocated some 25 miles

of mainline, serving Warrior for some

more years from the south by connecting

another old mine spur to the new

mainline.

Eventually the spur to Warrior

from the south was abandoned.

And what of the old mainline to the north of Warrior? It was abandoned in 1914 and some years later the Highway Department built a road on the roadbed. That road is US-31 which is the address of the Top Hat Bar-B-Que next to Blount Springs in Hayden, AL. Now, the Top Hat didn’t open till 1967. So, maybe the old Pit Man wasn’t hearing things, all alone, in the early hours, after all. What do you think? Could we still hear it 100 years later?

|

|

|

|

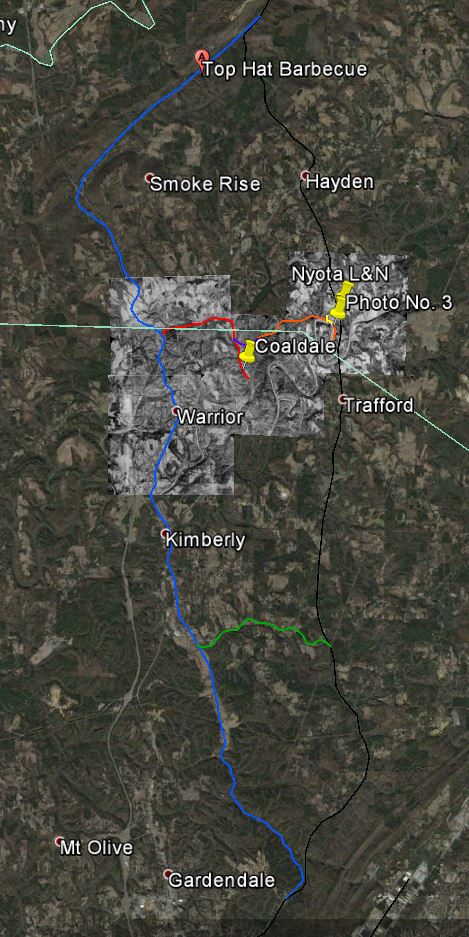

Google Earth overlay showing "old" L&N main line in blue, spur tracks to various industries and mines in red. The purple segment is thought to be the original spur to the Mabel mines, Mabel Mining Company shown on Kelly's 1905 map. The "Louise" tramway is shown in yellow. |

Larger view showing "old" L&N main in blue and "new" L&N main in black. |