L&N Relocation: Two Tracks or Not Two Tracks

|

|

Brocks Gap Tunnel, 2004 |

|

|

CSX train crossing the Mulberry Fork Warrior River [Photo https://bridgehunter.com/al/cullman/bh48984/}River

|

This material was originally prepared by the author for the Mid South Chapter R&LHS Newsletter, the Flyer. The author would like to acknowledge the help of the late Lyle Key as well as Thomas Denney and editor Marv Clemons who provided information and graphics from their collections. Due to space constraints in The Flyer, additional graphics and narrative are included here which were not able to be included in The Flyer.

f

you are a student of Birmingham’s

history you know that it was founded at

the junction of two railroads to be a

New South Industrial City.

And you likely know that in

post-civil war Alabama, there was

precious little capital for the building

of railroads in 1870.

The S&NA had been saved from

bankruptcy only by the efforts of James

Sloss’ Nashville and Decatur RR

(N&D) being offered, along with the

unfinished S&NA to the L&N RR in

a long term lease including the

requirement that the L&N complete

the railroad through the hills and

valleys of north Alabama.

According

to Chief Engineer John Milner’s son,

as noted in Armes “Story of Iron and

Coal in Alabama”, Milner would direct

the layout of the line north of

Birmingham to have “more curves, more

curves and more stiff grade”, in order

to save money.

Milner’s wife is quoted in the

same story as saying “that was not the

way my husband planned it, nor the way

he wanted it.

It was the way he just had to

make it.”

The Need for Improvements

Birmingham

did grow and prosper to the point that

the original line was inadequate.

In 1907, L&N President Milton

Smith addressed a committee of the

Alabama legislature describing the

situation in which the L&N

Railroad’s South & North Alabama

Subdivision found itself.

This address was part of an

ongoing battle royal between the L&N

and the Alabama Legislature over rates,

but that is another story. Smith stated,

“Take the North and South

Alabama as an illustration.

It is a road originally built

with limited capital through a rugged

country across drainage, and when opened

for traffic there was not a community of

100 persons on the line between

Montgomery and Decatur.

The Alignment is crooked and the

grades excessive, equivalent to more

than 80 feet to the mile [1.5%].

The heaviest locomotive in use,

having a tractive power of 35,000 lbs.

can move but 740 train tons.”

|

||

|

This is believed to be the original S&NA bridge over the Locust Fork near Warrior, AL. Note the approach spans are wooden and the main span is a Fink Truss. The piers appear to be the same as the image on the right, except caps. The piers are still standing, c. 2020. Image from Jim Bennett collection. |

This is believed to be the rebuilt bridge over the Locust Fork. Here the approach spans appear to be an iron trestle work, and the main span is a heavier deck truss. Image from Warrior, AL Facebook page. |

1895 Track Chart from Ken Penhale notes that the bridge was rebuilt in 1887 with a "205', 6" Iron V Deck and 24" beams N&S Approach, 38 spans 15'-10" each". |

Smith’s

point was to seek to have the

legislators understand that railroads

must be able to respond to traffic

demands if they are able to support

shipper’s needs and that improvements

cost money.

By

the time that Milton Smith was before

the legislative committee in Montgomery,

the L&N had already double tracked

14 miles

through Birmingham from Black

Creek south to Oxmoor. Most of this work

was done near original location with

moderate adjustments in alignment and

curvature.

Likewise work had been done from

Decatur south to Flint about 5 miles in

north Alabama, and from Calera south to

Hardy [near Alabaster] about 13 miles

providing double track, passing sidings

and terminal facilities as reported in

the Railroad Gazette.

This included old Boyles Yard

opened in 1904.

Smith outlined these recent improvements to the legislators but stated,

“traffic now pressing is greater than can be moved and if the present volume of traffic is to be continued and increased, it will be necessary to reconstruct the line, reduce grades and curvature, lay second tracks… the work of reducing grades and laying second track between Oxmoor and [Alabaster], 14.4 miles has been begun at an estimated cost of $1 million.”

Smith

went on to say that the other needed

improvements between Montgomery and

Decatur would cost $15 million. Smith

finished by saying that if capital could

not be obtained “the carrier must

restrict its traffic to existing

facilities, that is, must refuse to

undertake to move traffic in excess of

its facilities.”

Birmingham’s growth would stop.

Of

interest from an engineering standpoint

is what and how the improvements were

made.

Fortunately the railroad press of

the day has provided great information.

The

project mentioned above, between Oxmoor

and Hardy [near Alabaster] included a

new crossing of the Cahaba River and

Shades Mountain.

The old line had been completed

before the Civil War to the south foot

of Shades Mountain at Sydenton; the 75

foot deep cut through the mountain was

not completed until about 1870.

The new line was completed in

1908 and involved relocating the

mainline, a new bridge over the river

and a tunnel at lower grades through

Shades Mountain to replace the deep cut

[now mostly filled in]. This project is

covered in this website under the

heading of Brocks

Gap, Gateway to Birmingham.

It is noted above that improvements had been completed from Black Creek south through Birmingham to Oxmoor. Black Creek is north of Boyles Yard and near New Castle, John Milner’s coal development built to assist the fledgling S&NA to develop new traffic. From New Castle northward the original line swung to the northwest along Cunningham Creek and passed through some of the earliest coal mining areas of Birmingham at Morris and Warrior, crossing the Locust Fork of the Warrior River and traversing valleys and Reid's Gap to gain ground over the ridges, crossing the Mulberry Fork of the Warrior River toward Cullman.

|

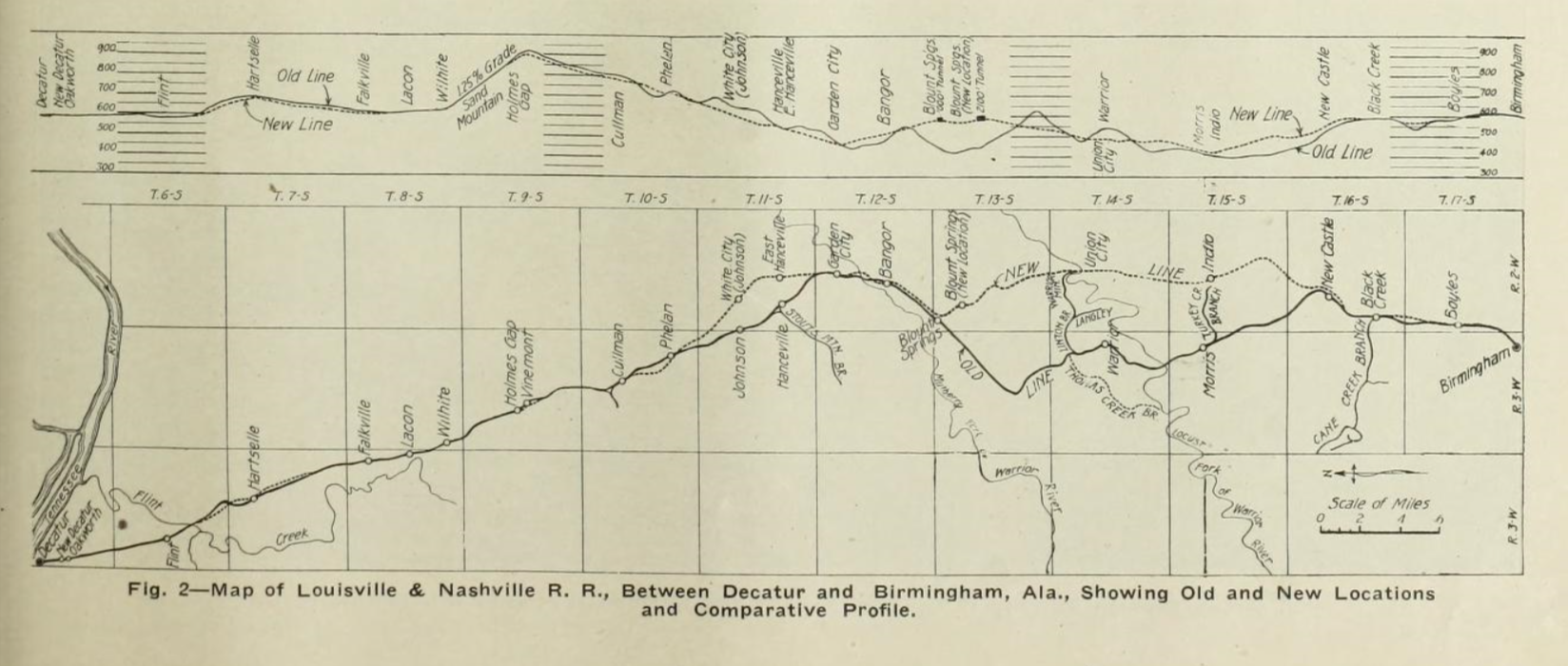

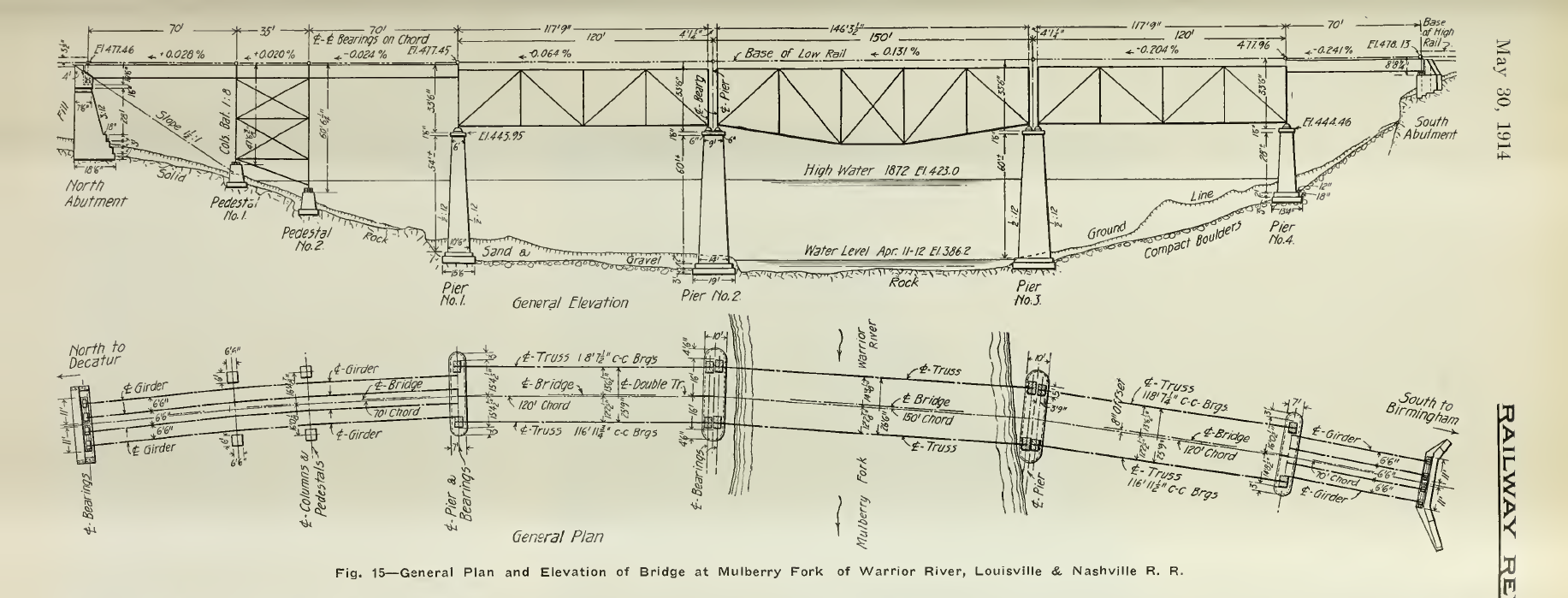

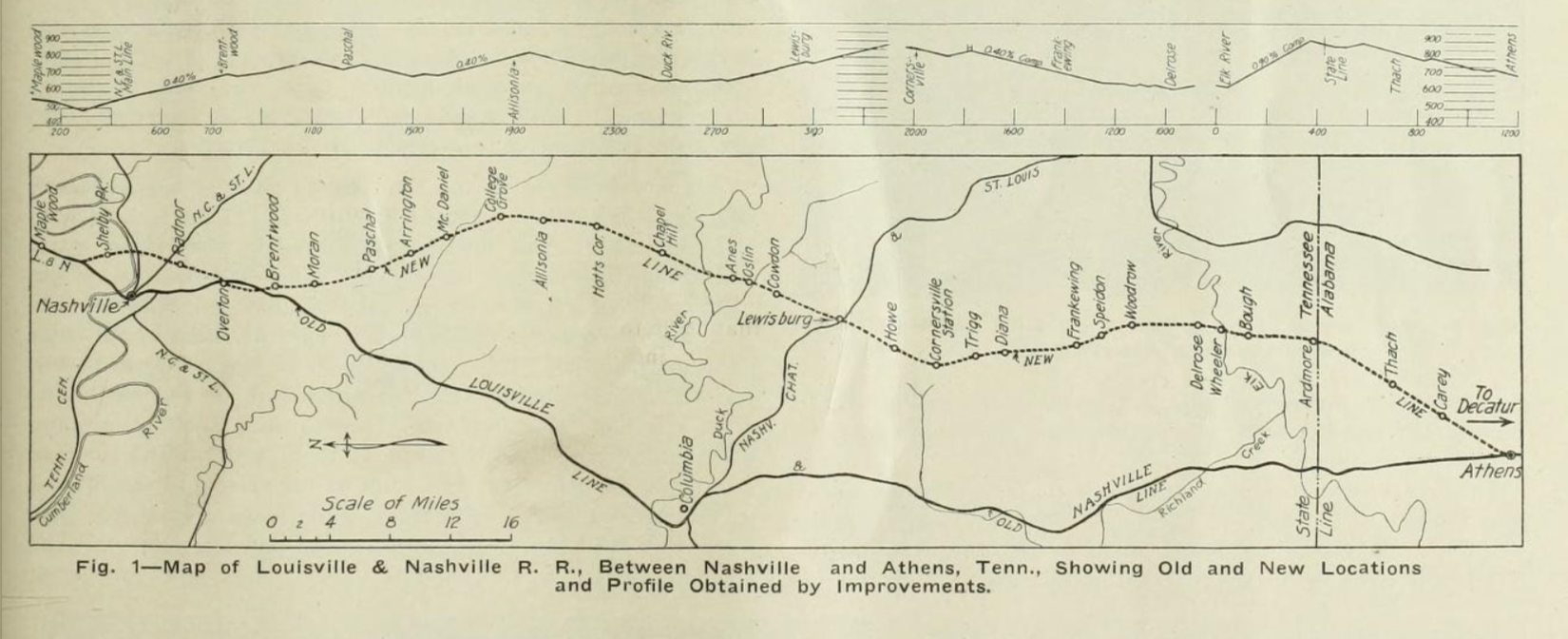

| The relocation and grade revisions are shown in this image for an article in Railway Review magazine May 9, 1914. Note the 1.25% Sand Mountain grade which is still a helper district today. There are two river bridges and two tunnels. |

It is in this area that the L&N completed one of the most ambitious improvements between Birmingham and Decatur. This was part of a larger “grade revision” project that extended from just north of Nashville, TN, south to Decatur, and then on south through Birmingham to Calera.

Athens

to Decatur

Athens

to Decatur

From

Athens to Decatur the line was

relatively flat but on swampy terrain

near the Tennessee River.

Bids received were higher than

the L&N wanted to pay, so this line

was built by company forces.

Equipment was acquired for

$85,000 which included a self-propelled

Atlantic Steam Shovel, 10 air operated

dump cars, a modified tender to serve

the shovel and provide a workshop

platform, an all steel Bucyrus pile

driver, a Jordan spreader, and a caboose

workshop car.

This work train used small locomotives to shuttle the dump cars as required. The Atlantic shovel was self-propelled and equipped with air brakes. According to “The Excavating Engineer” this outfit was very successful and saved enough money compared to bids received to pay for the equipment. The picture at right is from the Excavating Engineer, April, 1914. The total excavation on this line segment was 385,000 cubic yards at the “Tanner cut” which was then used to build new fill on the swamp areas north of the Tennessee River.

The

L&N didn’t have a bridge over the

Tennessee River at Decatur; L&N [then

and now] had trackage rights over the

[Norfolk] Southern’s bridge.

The new line improved the bridge

approach location on the north side of

the river for L&N. On the

south side of the Tennessee River,

L&N had already built extensive

facilities at New Decatur, south of

Decatur including yards and shops. South

of Decatur for the first 20 miles the

work was not remarkable.

It did improve grades and

alignment to

some degree.

If

you drive I-65 frequently, north of the

Lacon exit, you may have noticed a

siding in the trees on the east side of

the interstate that often holds a

locomotive.

This is the pusher for the

controlling southbound grade on the

L&N at Sand Mountain from Wilhoite

to Holmes Gap..

The grade was and is 1.25%; civil

engineers at the time couldn’t find a

way to avoid it.

The SB

pusher grade up the mountain is

about 5 miles long.

On

the south side of the mountain, the

northbound grade is about 12 miles, but

at a more manageable grade of 0.5%. The

town of Cullman is located on this

segment of line.

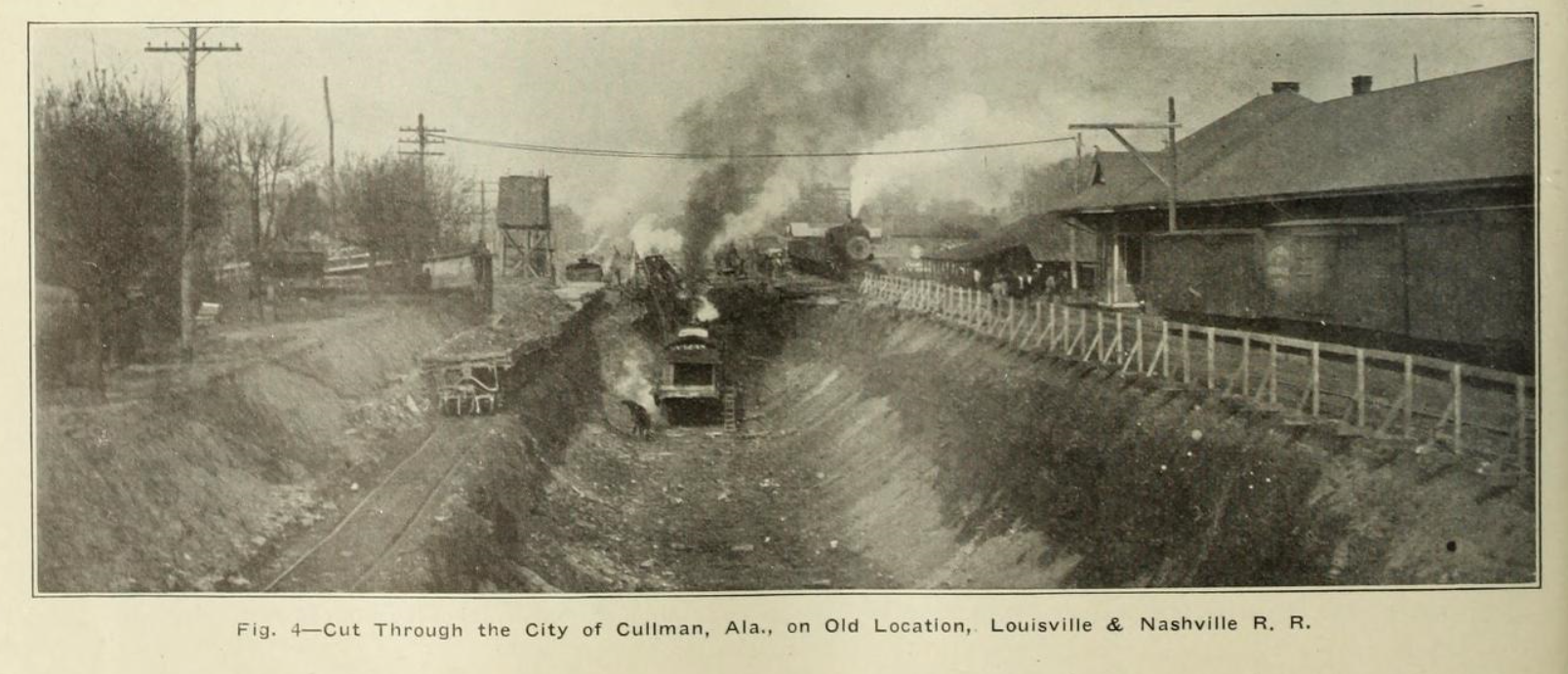

Here the L&N decided to lower

the old line some 20 feet right through

town.

This required staged

construction, relocation of the station

and freight house and the construction

of 5 street overpasses.

These 5 overpasses were reinforced concrete with sidewalks on each side. The loading was designed for a 35,000 lb. road roller plus 100 lb. per square foot. Today 3 of the original bridges over the railroad are still in use, but are posted at 10 Ton total weight, including school buses. [Note that a full size school bus weighs about 16 tons empty!] These overpasses are still standing in 2020.

Cullman

to Birmingham

South

of Cullman there were significant

engineering issues to be addressed.

Most of the old line from Cullman

to Birmingham was relocated to a

completely new alignment.

Much of the remaining line was

changed vertically so that for practical

purposes, it was all new line.

The

primary obstacles were the ridges at

Blount Mountain and Hayden, the climb to

these ridges and the major water

crossings at Mulberry Fork and Locust

Fork of the Black Warrior River as well

as the crossing of Gurley Creek.

In addition there were many

smaller streams and creeks to cross.

It

is worthy of note that when the original

line of the South & North Alabama

was planned in the 1850’s, it was

determined that it would be a line

crossing ridge and valley terrain.

The mineral wealth of this

district was well known and Chief

Engineer John Milner knew that the

original investment for the main line

would be great, but that the extension

of spurs and branch lines to the future

mines would be easier to build when the

time came.

The original competitor of the

South & North, the Alabama &

Tennessee River connected Meridian MS

with Chattanooga and followed a much

easier valley route for much of it’s

length.

As it turned out, that line,

which became the Alabama Great Southern

did not achieve nearly the raw material

traffic from the mines of the Birmingham

District as the L&N.

The

new line and grade was planned to climb

the side of Blount Mountain, heading

southwest.

This line followed the original

line but at higher elevation to ascend

the “mountain”.

After climbing the line turned

south and two tunnels were bored.

The first, Blount Mountain, is

about 1000 feet long and is unlined,

being in good rock.

The tunnel was built from the

bottom up, that is, the boring started

at the track level and worked upward as

forward progress was made.

The

second tunnel, at Hayden, is about 2100

feet long but was in less sound rock and

had to be concrete lined.

It was built from near the top

and then excavated down to the floor as

forward progress was made.

The roof was lined and then then

as work progressed downward the sides

are cut and lined; the upper portion has

a footing behind the top of the side

walls.

The south end of the Hayden

tunnel encountered such poor rock that

the portal was built about 150 feet into

daylight, the tunnel constructed and

then filled to prevent slides from

coming over the top of the portal.

It

is interesting to note that compressed

air was used for drilling equipment and

that the contractor had an air

compressor plant on the old line, using

iron pipe to take the compressed air to

Blount tunnel and then on to Hayden, a

total distance of about 3 miles.

South of Hayden tunnel, the line followed a ravine and stream bed going downhill towards the south. The tunnel material was used to build a long fill coming down the south side of the mountain.

River

Crossings

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

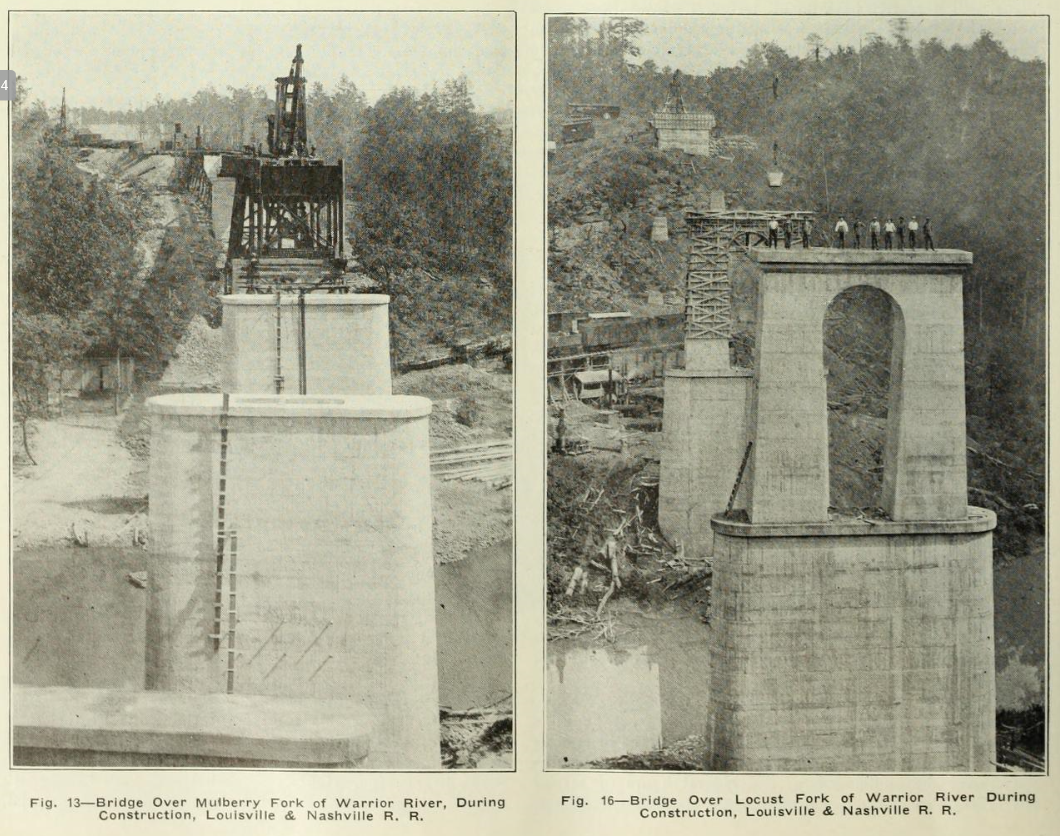

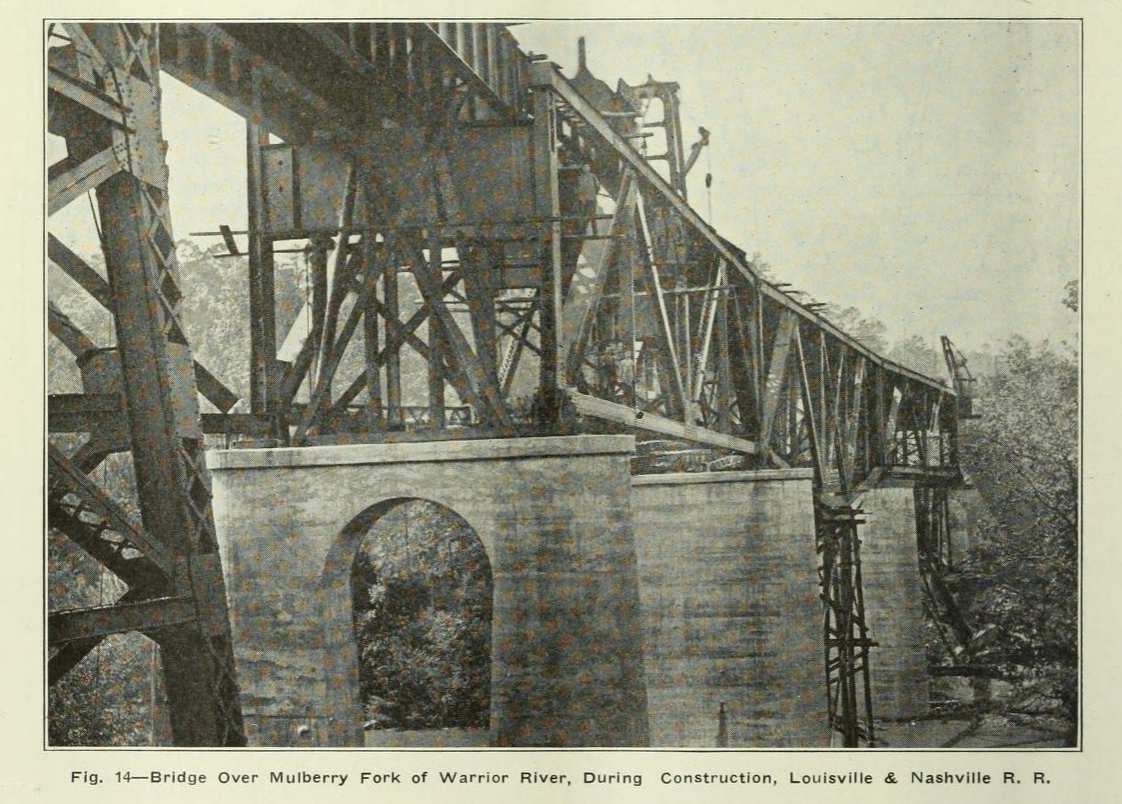

The

three major water crossings mentioned

above are still standing.

The Mulberry Fork bridge is north

of the two tunnels described above.

It consists of three girder

spans, three deck truss spans and a

girder span, all open deck and all on a

3o

curve.

The spans are

70’-35’-70’-118’-146’-118-70’

(rounded).

The concrete piers for the truss

spans are about 60 feet tall.

This handsome bridge is visible

from the old highway looking east, and

has a curved lower cord on the main

truss span.

[Photo is from https://bridgehunter.com/al/cullman/bh48984/}

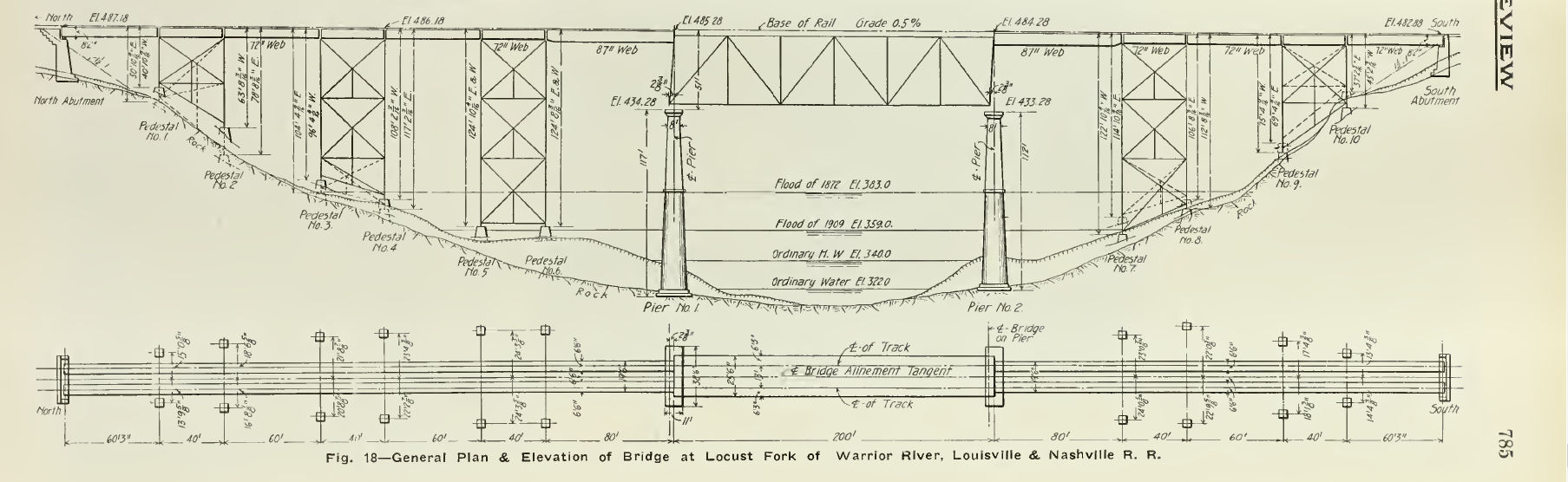

The

Locust Fork bridge is on tangent

alignment and is also a combination of

one deck truss span with deck girder and

tower approaches.

The span arrangements are

60’-40’-60’-40’-60’-40’-80’-200’-80’-40’-60’-40’-60’

(rounded).

The concrete piers for the truss

span are about 115’ tall.

The

third major structure on the relocated

route is at Gurley Creek.

This is a tower trestle structure

with 7 plate girder spans and 6 @ 40’

tower spans.

The

span arrangements are

70’-40’-60’-40’-60’-40’-60’-40’-60’-40’-60’-40’-70’

for a total length of 680 feet.

A

number of concrete arch spans were

constructed as part of this project;

concrete had certainly come into its own

by this time period.

Earlier structures would have

been constructed of cut stone masonry,

including arches.

These may be found on the

original routes of the S&NA as well

as the N&D, as well as stacked stone

box structures.

The Ross Bridge stone arch

culvert in Hoover, AL, has become

“famous”.

These improvements were completed by the time the United States entered WWI. Railroad operations continued through the twenties and lanquished through the depression years. Then the onset of WWII brought growth in traffic and industrial development.

Improvements

in Tennessee

Briefly,

the project in Tennessee included a new

line to bypass Nashville, cross the

Cumberland River on a major high bridge

which still stands above Shelby Park,

build Radnor Yards north of Brentwood

[south of Nashville], and a new grade at

present day Brentwood which lowered the

line 45 feet, and may still be seen

adjacent to the Brentwood interchange on

I-65.

From Brentwood the L&N built a new route 98 miles south to Athens, AL. This “new line” would supplement the original Nashville & Decatur RR (N&D) built before the Civil War by James Sloss. The new line included two tunnels and a pusher district of 0.9% for some 6 miles. The new line was planned for freight traffic so the old N&D line could be used for mostly passenger traffic and local freight. This effectively created a double track line from Nashville to Athens although on separate locations some mile apart.

|

|

The relocation and grade revisions are shown in this image for an article in Railway Review magazine May 9, 1914. The "old" line was the original Nashville & Decatur built for James Sloss before the Civil War. |

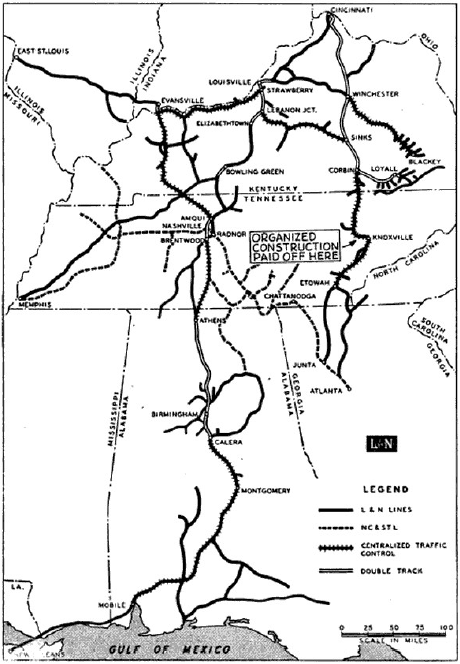

CTC and Back to Single Track

|

Seeking new operating efficiencies, the L&N implemented Centralized Train Control (CTC) which involves the use of electro-mechanical systems to enable one operator to control signals and track switches (turnouts) on a large segment of railroad. According

to Murray Klein’s “The

History of the Louisville &

Nashville Railroad”, the

L&N’s first CTC

installation was the 96 miles

between Brentwood, TN, south of

Radnor Yards near Nashville to

Athens, AL..

This improvement was

accomplished in June, 1942.

Subsequent installations

focused on single track lines,

as shown on this 1956 map from

Railway Signaling magazine. Typically,

installation of CTC on single

track lines enabled fewer

passing sidings, fewer block and

siding signals, and less

operating and maintenance staff.

The image at left shows a

CTC panel at Birmingham.

This display is located at the

Heart of Dixie RR Museum in

Calera, AL, south of metro

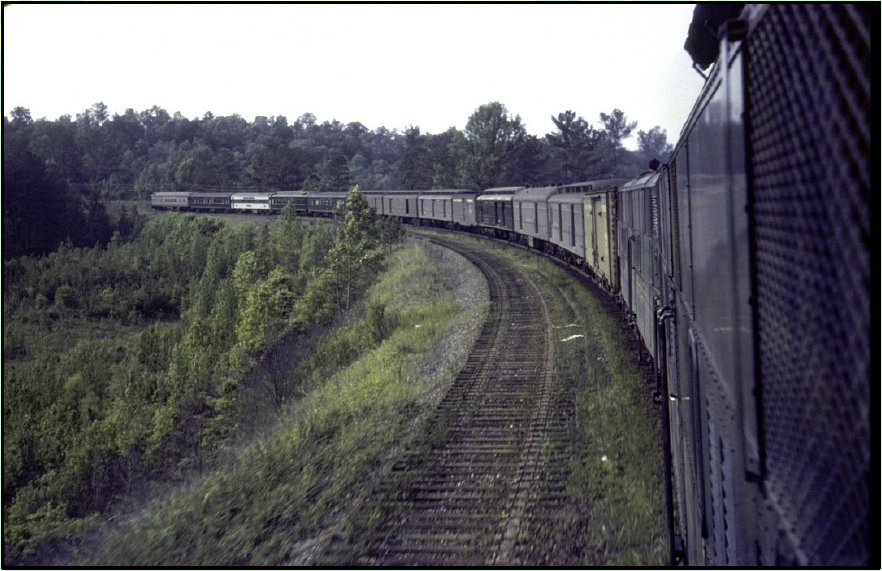

Birmingham. The double track between Athens and Calera in Alabama was one of the last segments to receive CTC. As was typical, the efficiencies of CTC enabled the railroad to remove double track, and this was accomplished by 1963 (Klein) when the entire mainline from Cincinnati to New Orleans was under CTC control. Ironically, when CTC was finally installed between Athens and Calera, the need for the double track main line was eliminated. Once the CTC system was in place and working, the railroad began removing the second track installed between 1908 and 1915. In the image at the lower left, from Marv Clemons' collection, we see the results of the removal of double track south of Calera, AL, after the installation of CTC. |

|

|

|

|

|